Week 12 - Rosenzweig-MacArthur predator-prey model and May’s complexity-stability relationship

Part 1: Rosenzweig–MacArthur predator–prey model

In this lab we are going to analyze the Rosenzweig–MacArthur predator–prey model:

\[\begin{align*} \frac {dN}{dt} &= rN(1-\frac{N}{K})-a\frac{N}{1+ahN}P\\ \frac {dP}{dt} &= ea\frac{N}{1+ahN}P-dP,\\ \end{align*}\] where \(r\) is the intrinsic growth rate of prey, \(K\) is the carrying capacity of prey, \(a\) is the rate of prey being consumed by predator, \(h\) is the handling time of predator, \(e\) is the assimilation rate of predation and \(d\) is the mortality rate of predator. The ZNGIs of \(N\) are \[ N = 0 \text{ and } P = \frac{r}{a}(1-\frac{N}{K})(1+ahN) \] and the ZNGIs of \(P\) are \[ P = 0 \text{ and } N = \frac{d}{a(e-dh)} \] The coexistence equilibrium is \(E_{np} = \left(N^* = \frac{d}{a(e-dh)}, P^* = \frac{r}{a}(1-\frac{N^*}{K})(1+ahN^*)\right)\).

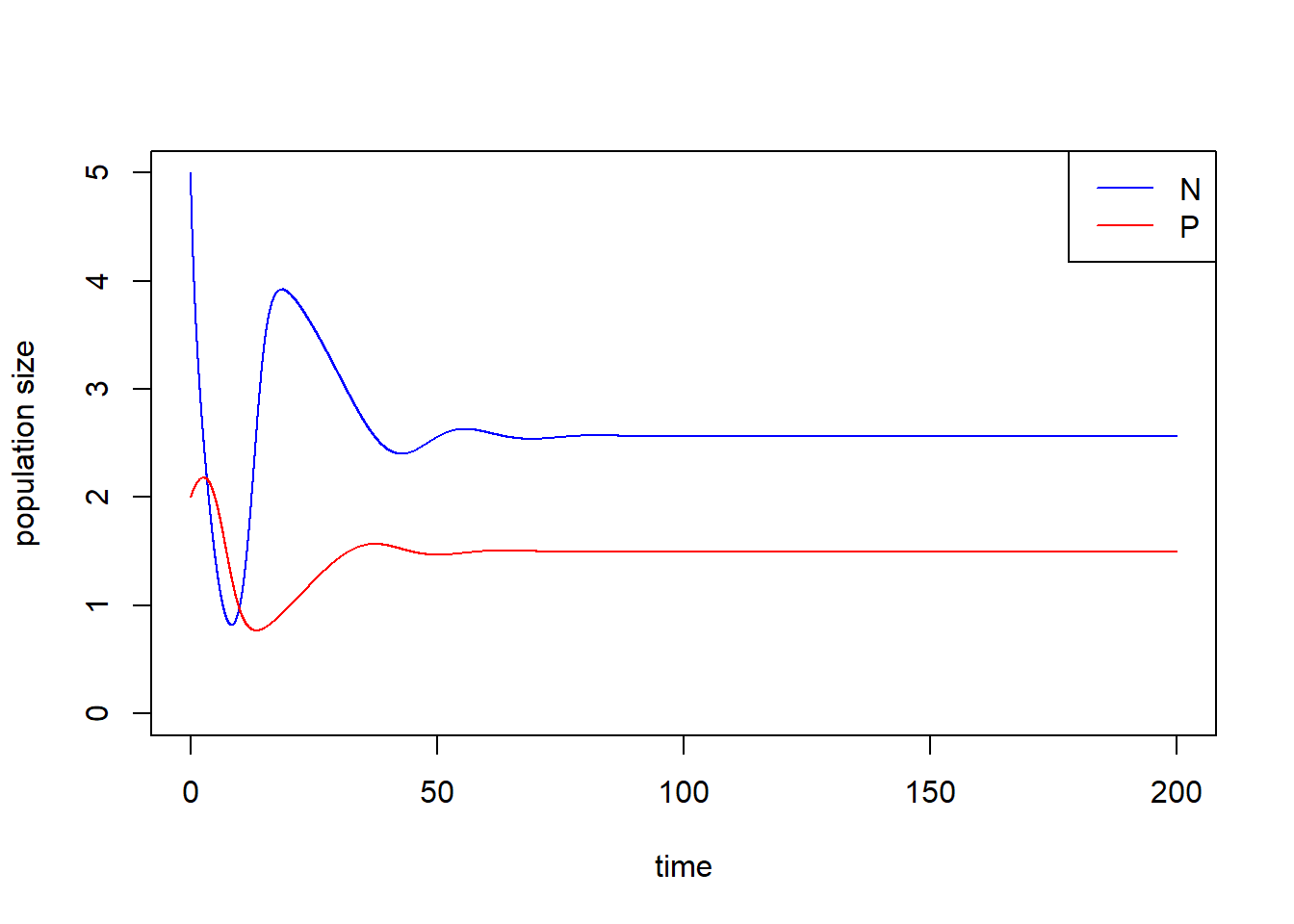

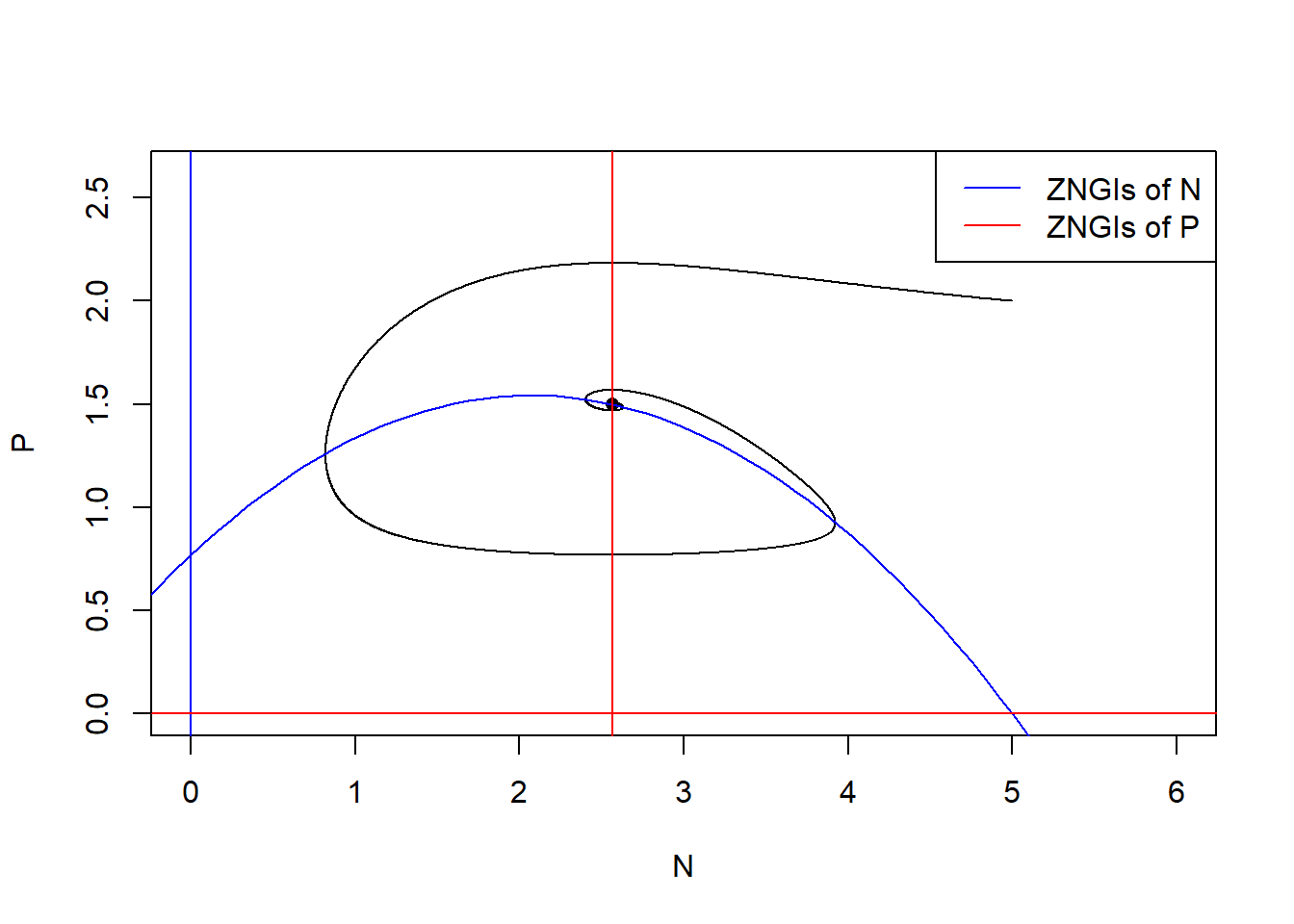

Please simulate the model using the parameter set (\(N_0\) = 5, \(P_0\) = 2, \(r\) = 1.0, \(K\) = 5.0, \(a\) = 1.3, \(h\) = 0.9, \(e\) = 0.6, \(d\) = 0.5) and plot the population trajectories of predator and prey as well as show their population dynamics in the state-space diagram.

library(deSolve)

### Model specification

RM_predation_model <- function(times, state, parms) {

with(as.list(c(state, parms)), {

dN_dt = r*N*(1-(N/K))-(a*N/(1+a*h*N))*P

dP_dt = e*(a*N/(1+a*h*N))*P-d*P

return(list(c(dN_dt, dP_dt)))

})

}

### Model parameters

times <- seq(0, 200, by = 0.01)

state <- c(N = 5, P = 2)

parms <- c(r = 1.0, K = 5.0, a = 1.3, h = 0.9, e = 0.6, d = 0.5)

### Model application

pop_size <- ode(func = RM_predation_model, times = times, y = state, parms = parms)

### equilibrium

E_np <- with(as.list(parms),

c(N = d/(a*(e-d*h)),

P = r/a*(1-d/(a*(e-d*h))/K)*(1+a*h*d/(a*(e-d*h)))))

### Visualize the population dynamics

# population trajectories

plot(c(0, max(times)), c(0, max(pop_size[, c("N", "P")])), type = "n", xlab = "time", ylab = "population size")

lines(N ~ time, data = pop_size, col = "blue") # dynamics of N

lines(P ~ time, data = pop_size, col = "red") # dynamics of P

legend("topright", legend = c("N", "P"), col = c("blue", "red"), lty = 1)

# state-space diagram

max_P <- max(pop_size[ ,"P"])

max_N <- max(pop_size[ ,"N"])

plot(P ~ N, data = pop_size, type = "l", xlim = c(0, max_N*1.2), ylim = c(0, max_P*1.2))

points(E_np["P"] ~ E_np["N"], pch = 16) # equilibrium

with(as.list(parms), {

# ZNGIs of N

abline(v = 0, col = "blue")

curve(r/a*(1-x/K)*(1+a*h*x), from = -2, to = K+2, col = "blue", add = T)

# ZNGIs of P

abline(h = 0, col = "red")

abline(v = d/(a*(e-d*h)), col = "red")

})

legend("topright", legend = c("ZNGIs of N", "ZNGIs of P"), col = c("blue", "red"), lty = 1)

Remark: with() is a function that you can load the value in the object without subsetting.

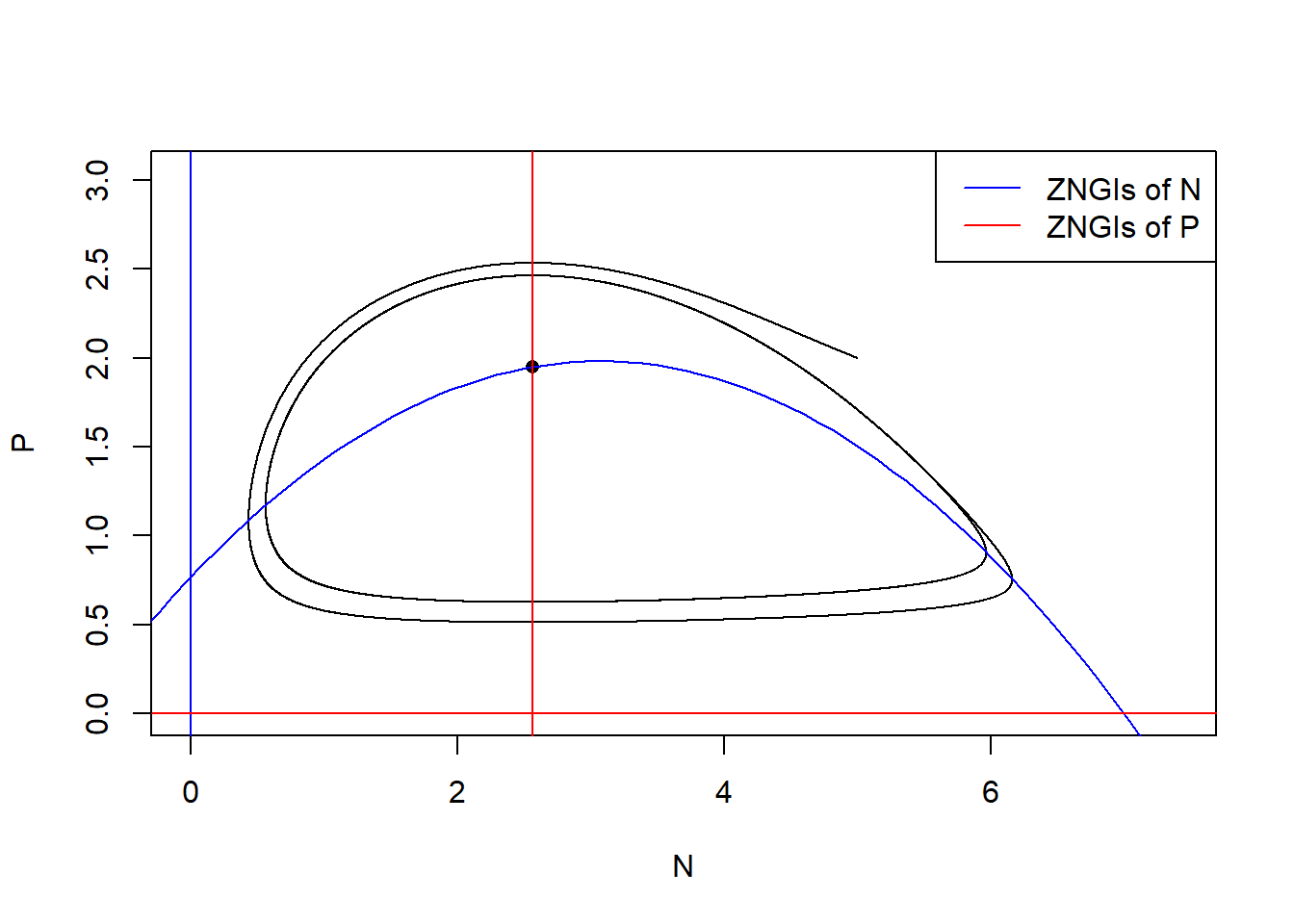

Now we increase the carry capacity \(K\) to show the paradox of enrichment. Let’s consider \(K = 7\) with other parameters fixed.

### Model parameters

times <- seq(0, 200, by = 0.01)

state <- c(N = 5, P = 2)

parms <- c(r = 1.0, K = 7.0, a = 1.3, h = 0.9, e = 0.6, d = 0.5)

### Model application

pop_size <- ode(func = RM_predation_model, times = times, y = state, parms = parms)

### equilibrium

E_np <- with(as.list(parms),

c(N = d/(a*(e-d*h)),

P = r/a*(1-d/(a*(e-d*h))/K)*(1+a*h*d/(a*(e-d*h)))))The population size of \(N\) and \(P\) do not stay at the equilibrium but cycle.

### Visualize the population dynamics

# population trajectories

plot(c(0, max(times)), c(0, max(pop_size[, c("N", "P")])*1.2), type = "n", xlab = "time", ylab = "population size")

lines(N ~ time, data = pop_size, col = "blue") # dynamics of N

lines(P ~ time, data = pop_size, col = "red") # dynamics of P

legend("topright", legend = c("N", "P"), col = c("blue", "red"), lty = 1)

# state-space diagram

max_P <- max(pop_size[ ,"P"])

max_N <- max(pop_size[ ,"N"])

plot(P ~ N, data = pop_size, type = "l", xlim = c(0, max_N*1.2), ylim = c(0, max_P*1.2))

points(E_np["P"] ~ E_np["N"], pch = 16) # equilibrium

with(as.list(parms), {

# ZNGIs of N

abline(v = 0, col = "blue")

curve(r/a*(1-x/K)*(1+a*h*x), from = -2, to = K+2, col = "blue", add = T)

# ZNGIs of P

abline(h = 0, col = "red")

abline(v = d/(a*(e-d*h)), col = "red")

})

legend("topright", legend = c("ZNGIs of N", "ZNGIs of P"), col = c("blue", "red"), lty = 1)

Do the long-term average of the population size equal to the equilibrium? Let’s calculate the long-term average of population size by function pracma::findpeaks(). It returns a matrix where each row represents one peak found. The first column gives the height, the second the position/index where the maximum is reached, the third and forth the indices of where the peak begins and ends — in the sense of where the pattern starts and ends.

library(pracma)

# find time points when local peaks occur

peaks <- findpeaks(pop_size[, "N"])[ ,2]

peaks ## [1] 2219 5694 8960 12225 15490 18755# get period as time between peaks

periods <- peaks[length(peaks)] - peaks[length(peaks) - 1]

# long-term average of N

avg_N <- mean(pop_size[(length(times) - periods + 1):length(times), "N"])

avg_N## [1] 3.642661# long-term average of P

avg_P <- mean(pop_size[(length(times) - periods + 1):length(times), "P"])

avg_P## [1] 1.4757## N P

## 2.564103 1.949845We show that the the long-term average of the population size of \(N\) and \(P\) are not identical to the equilibrium of \(N\) and \(P\). In fact, the long-term average of the resource \(N\) is larger than the original equilibrium due to the fact that the per capita growth rate of the \(P\) is a concave-downward function.

What will happen if you add a perturbation to the system (i.e., change the initial conditions)? Try out different values of \(N_0\) and \(P_0\) and visualize the differences in the state-space diagram.

Shiny app is credit to Gen-Chang Hsu

Part 2: Bifurcation diagram

Here, we simulate the bifurcation diagram along the prey carrying capacity. Different from previous bifurcation plots, our analytical analyses told us that this model may end up in a cycle. Therefore, we need to (1) identify whether the final state is cycling (i.e., based on the variance of the time series) and, if so, (2) find the cycle and store the long-term average across multiple cycles.

library(tidyverse)

#### (1) Specify parameters

times <- seq(0, 1500, by = 1)

state <- c(N = 1, P = 1)

parms <- c(r = 1.0, K = 5.0, a = 1.3, h = 0.9, e = 0.6, d = 0.5)

r = as.numeric(parms["r"])

K = as.numeric(parms["K"])

a = as.numeric(parms["a"])

h = as.numeric(parms["h"])

e = as.numeric(parms["e"])

d = as.numeric(parms["d"])

#### (2) Create vector for K and saving space

K.vector <- seq(from = 0.1, to = 9.0, by = 0.05)

N.sim <- length(K.vector)

Data <- as.data.frame(matrix(0,

nrow = N.sim * 2, # one for N, one for P

ncol = 7))

names(Data) <- c("Variable", "MeanDensity", "MinDensity", "MaxDensity",

"Variation", "K", "Dynamic")

#### (3) Run the simulation for each K within the vector

for(i in 1:N.sim){

## Run the simulation with updated K value

parms["K"] <- K.vector[i]

Temp <- ode(func = RM_predation_model, times = times, y = state, parms = parms)

## Only use the last 300 time steps of the simulation

Temp <- as.data.frame(Temp[1200:1500, ])

## If there is no fluctuation, can freely use all final steps

if(var(Temp$N) < 1e-5){

Temp.use <- Temp

Temp.use$K <- parms["K"]

Temp.use$Dynamic <- "Stable"

}

## If there is fluctuation, need to get accurate cycle start-end point

if(var(Temp$N) > 1e-5){

peaks <- pracma::findpeaks(Temp[, "N"])[ ,2]

Temp.use <- Temp[(peaks[1] : peaks[length(peaks)]), ]

Temp.use$K <- parms["K"]

Temp.use$Dynamic <- "Cycle"

}

## Use tidyverse to wriggle data

Temp.tidy <-

Temp.use %>%

gather(key = Variable, value = Density, -c(time, K, Dynamic)) %>%

group_by(Variable) %>%

summarise(MeanDensity = mean(Density),

MinDensity = min(Density),

MaxDensity = max(Density),

Variation = var(Density),

K = unique(K),

Dynamic = unique(Dynamic))

## Save simulation summary into Data

Data[(i-1)*2 + c(1:2), ] <- Temp.tidy

}

#### (4) Plot

Data %>%

ggplot(aes(x = K, color = Variable)) +

geom_hline(yintercept = 0) +

geom_vline(xintercept = d / (a * (e - h * d)),

linetype = "longdash", col="grey") +

geom_vline(xintercept = (e + d * h) / (a * h * (e - d * h)),

linetype = "longdash", col="grey") +

geom_line(data = Data[Data$Dynamic == "Stable", ],

aes(y = MeanDensity)) +

geom_line(data = Data[Data$Dynamic == "Cycle", ],

aes(y = MeanDensity),

linetype = "dotted", alpha = 0.5) +

geom_line(data = Data[Data$Dynamic == "Cycle", ],

aes(y = MinDensity),

linetype = "dashed") +

geom_line(data = Data[Data$Dynamic == "Cycle", ],

aes(y = MaxDensity),

linetype = "dashed") +

labs(x = "K", y = "Equilibrium value") +

scale_color_manual(values = c("N" = "blue", "P" = "red")) +

theme_classic() +

theme(legend.position = "bottom")

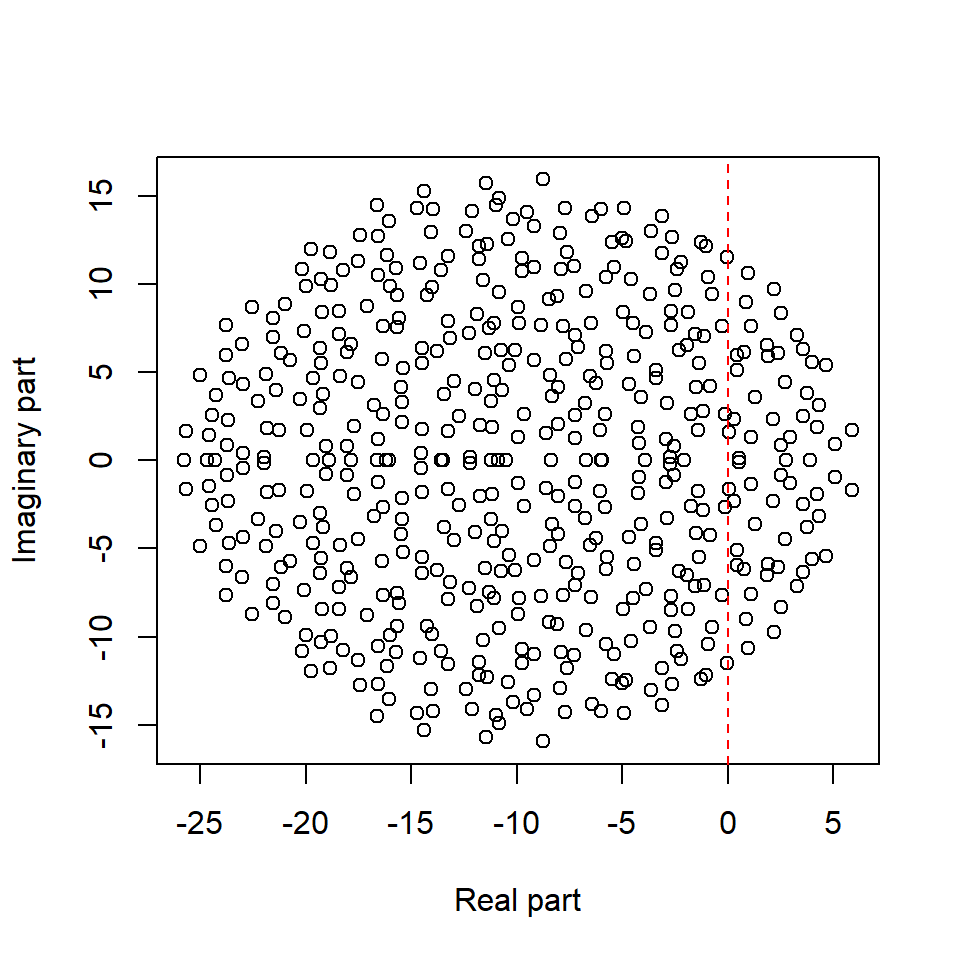

Part 3: May’s complexity-stability relationship

May’s insight was to skip the Jacobian calculation altogether and directly consider the Jacobian matrix as a large random matrix (\(\mathbf{M}\), with elements \(m_{ij}\)) resting at a feasible equilibrium, and then the eigenvalues of the Jacobian matrix could be derived based on random matrix theory.

Let’s try to recreate May’s random matrix. In particular, May considered the following algorithm to build the random Jacobian matrix for \(S\) species (thereby a \(S \times S\) matrix):

Here, \(C\) represents the connectedness of the system (chance of species interacting with each other), \(\sigma^{2}\) can be considered as the realized interaction strengths, and \(d\) is the strength of self-limitation.

# code for building May's random matrix

BuildMay = function(S, C, d, sigma){

# fill the whole matrix

entry <- rnorm(S * S, mean = 0, sd = sigma)

M <- matrix(entry, nrow = S, ncol = S)

# remove connections

remove <- matrix(runif(S * S) <= C, nrow = S, ncol = S)

M <- M * remove

sum(M != 0) / (S*S) # should equal to C

# substrate diagonal elements by d

diag(M) <- diag(M) - d

return(M)

}

May <- BuildMay(S = 500, C = 0.5, d = 10, sigma = 1)

EVals <- eigen(May)$values

Re.EVals <- Re(EVals)

Im.EVals <- Im(EVals)

plot(Re.EVals, Im.EVals, xlab = "Real part", ylab = "Imaginary part")

abline(v = 0, col = "red", lty = 2)

Extra reading: Elliptic raw

In May’s random matrix, the entries \(m_{ij}\), which represents the effect of species \(j\) on species \(i\)’s growth rate, are independently generated. However, in ecological networks, we usually model pairwise interaction such as consumer-resource, mutualism, and competition, in which cases, \(m_{ij}\) is not independent of \(m_{ji}\). For consumer-resources interactions, \(m_{ij}\) and \(m_{ji}\) are negatively correlated. For mutualism or competition interaction, \(m_{ij}\) and \(m_{ji}\) are positively correlated. Under the assumption that the pairwise interactions are correlated, we may show that the eigenvalues of the randomly generated Jacobian do not follow uniform distribution in a circle, but in an ellipse.

We build a function BuildElliptic with argument \(S\) is the number of species (i.e. the dimension of the Jacobian), \(C\) is the connectance, \(d\) is the strength of self-limitation, \(\sigma\) is the variance (i.e. the realized interaction strength) and \(\rho\) is the correlation of the pairwise interaction.

library(ggplot2)

#### The function to build Elliptic law

BuildElliptic <- function(S, C, d, sigma, rho){

# sample coefficients in pairs

pairs <- MASS::mvrnorm(n = S * (S-1) / 2,

mu = c(0, 0),

Sigma = sigma^2 * matrix(c(1, rho, rho, 1), 2, 2))

# build a completely filled matrix

M <- matrix(0, S, S)

M[upper.tri(M)] <- pairs[,1]

M <- t(M)

M[upper.tri(M)] <- pairs[,2]

# determine which connections to retain (in pairs)

Connections <- (matrix(runif(S * S), S, S) <= C) * 1

Connections[lower.tri(Connections)] <- 0

diag(Connections) <- 0

Connections <- Connections + t(Connections)

M <- M * Connections

# set diagonals

diag(M) <- diag(M) - d

return(M)

}# consumer-resources interactions

M_CR <- BuildElliptic(S = 500, C = 0.3, d = 10, sigma = 1, rho = -0.5)

EVals_CR <- eigen(M_CR)$values

Re.EVals_CR <- Re(EVals_CR)

Im.EVals_CR <- Im(EVals_CR)

# mutualism or competition

M_MC <- BuildElliptic(S = 500, C = 0.3, d = 10, sigma = 1, rho = 0.5)

EVals_MC <- eigen(M_MC)$values

Re.EVals_MC <- Re(EVals_MC)

Im.EVals_MC <- Im(EVals_MC)

# combine data

Re.EVals <- c(Re.EVals_CR, Re.EVals_MC)

Im.EVals <- c(Im.EVals_CR, Im.EVals_MC)

# visualization

plot(Re.EVals, Im.EVals, xlab = "Real part", ylab = "Imaginary part", type = "n")

points(Re.EVals_CR, Im.EVals_CR, col = "green")

points(Re.EVals_MC, Im.EVals_MC, col = "blue")

abline(v = 0, col = "red", lty = 2)

legend("topleft", legend = c("Resource-consumer", "Mutualism or Competition"), col = c("green", "blue"), pch = 1)

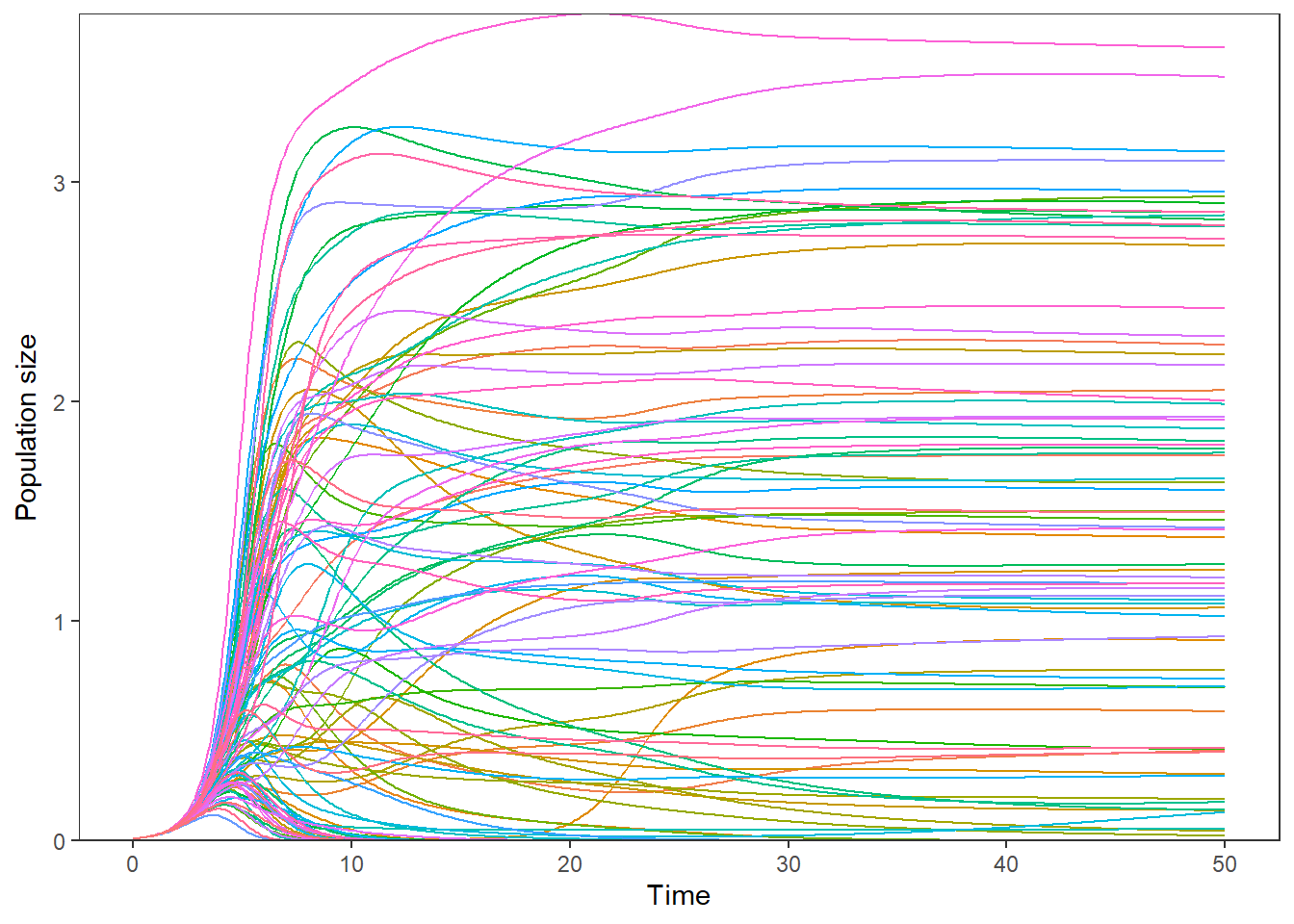

Extra reading: Simulating generalized Lotka-Volterra model

Now that you’ve learned the two-species Lotka-Volterra model, you may want to expand it to three species or more. For the three-species case, the model is simply:

\[ \dfrac{d N_1}{d t} = N_1(r_1 - \alpha_{11} N_1 - \alpha_{12} N_2 - \alpha_{13} N_3) \\ \dfrac{d N_2}{d t} = N_2(r_2 - \alpha_{21} N_1 - \alpha_{22} N_2 - \alpha_{23} N_3) \\ \dfrac{d N_3}{d t} = N_3(r_3 - \alpha_{31} N_1 - \alpha_{32} N_2 - \alpha_{33} N_3) \]

Expanding it to multi-species should also be fairly straightforward, as the population growth rate of each species \(i\) can be written as:

\[ \dfrac{d N_i}{d t} = N_i(r_i + \sum_{j=1}^{n} \alpha_{ij} N_j) \]

The above equation is called the generalized Lotka-Volterra model (GLV). Note that the sign before \(\alpha_{ij}\) is a plus sign, therefore, under this formulation, positive* \(\alpha_{ij}\) represents mutualistic interactions and negative \(\alpha_{ij}\) represents competitive interactions.

However, when coding the simulation, there is no way that you will explicitly type out 100 equations for a system with 100 species, nor will you explicitly prepare \(100 \times 100\) different \(\alpha_{ij}\) parameters. To efficiently simulate the system, we will “vectorize” our code by using vectors and matrices to represent our dynamical system. In particular, for the three-species case, the three equations can be written in matrix form as follows:

\[ \begin{pmatrix} \dfrac{d N_1}{d t}\\ \dfrac{d N_2}{d t}\\ \dfrac{d N_3}{d t}\\ \end{pmatrix} = \begin{pmatrix} N_1 & 0 & 0 \\ 0 & N_2 & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & N_3 \end{pmatrix} \begin{bmatrix} \begin{pmatrix} r_1 \\ r_2 \\ r_3 \end{pmatrix} - \begin{pmatrix} \alpha_{11} & \alpha_{12} & \alpha_{13} \\ \alpha_{21} & \alpha_{22} & \alpha_{23} \\ \alpha_{31} & \alpha_{32} & \alpha_{33} \\ \end{pmatrix} \times \begin{pmatrix} N_1 \\ N_2 \\ N_3 \end{pmatrix} \end{bmatrix} \]

You can try out the matrix multiplication to see how the above expression is equivalent to the first one. In the similar spirit, the multi-species GLV model can be written in matrix form as follows:

\[ \dfrac{d N}{d t} = D(N)[r + AN] \]

Here, N is a vector of population densities with elements \(N_i\) (length n), \(D(N)\) is a diagonal matrix with \(N_i\) on the main diagonal (dimension \(n\) * \(n\)), \(r\) is a vector of species’ intrinsic growth rates \(r_i\), and A is a matrix of interaction coefficients \(\alpha_{ij}\) (dimension \(n\) * \(n\)). With this notation, we can efficiently code the GLV with the following R script.

#### Lotka-Volterra model

GLV = function(times, state, parms){

with(as.list(c(state, parms)),{

dNX = diag(state) %*% (r + A %*% state)

return(list(c(dNX)))

})

}

#### Parameter setting with a random interaction matrix

n <- 100

r <- rep(1, n)

A <- matrix(rnorm(n * n, mean = 0, sd = 0.1), nrow = n, ncol = n)

diag(A) <- -1

parms = list(r = r, A = A)

times = seq(0, 50, by = 0.1)

ini= rep(0.01, n)

#### Run the simulation

out = as.data.frame(ode(func=GLV, y=ini, parms=parms, times=times))

#### Gather data for ploting

comp.gg = gather(out, key=state.var, value=count, -time)

#### Plot

ggplot(comp.gg,

aes(x=time, y=count, color=state.var)) +

geom_line() +

geom_hline(yintercept=0, linetype=1, color="black") +

scale_y_continuous(expand=c(0, 0)) +

ylab(expression(paste("Population size"))) +

xlab("Time") +

theme_bw() +

theme(legend.position="none",

plot.title=element_text(hjust=0.5),

panel.grid.major=element_blank(),

panel.grid.minor=element_blank(),

panel.background=element_rect(colour="black"))